home | tumblrblog | musics | electronics | ask | about | more

In order to bring everything together, let’s look at some common circuits that are found in many typical electric guitars.

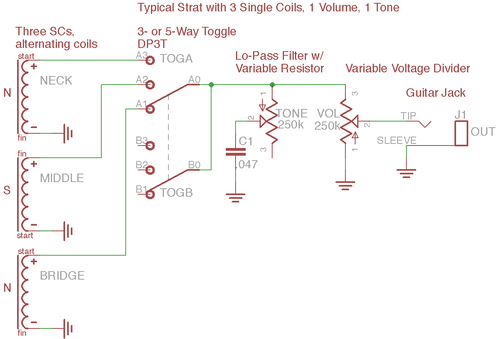

First up is this Start-style configuration. Three single coil pickups are in an alternating polarity, parallel configuration. The alternating polarity allows for some hum canceling to occur whenever the middle pickup is combined with either the neck or the bridge pickup. The DP3T toggle switch selects which pickup is passed to the rest of the circuit. The second “half” of this toggle switch is unused; it is common for manufacturers to stock one type of switch and use it in as many guitars as possible, rather than stock a switch for every application. The DP3T may be 3-way or 5-way; the 5-way version allows “in-between” selections to be made, allowing either the bridge and middle or middle and neck pickups to be combined at the switch.

The combined signal then flows to a junction with a potentiometer in a variable-resistor configuration. This variable resistor affects the amount of signal which gets affected by the lo-passing capacitor (this “lo-passing” qualifier refers to the signal that passes to the output of this part of the circuit; only high frequencies “pass” through capacitors). Either the resistance is high and the signal bypasses the tone circuit, or the resistance is low and some of the signal drops across this capacitor. Therefore, this potentiometer acts as a “tone” knob. The signal is then passed to another potentiometer which acts as a variable voltage divider. The full signal, part of the signal, or none of the signal drops across this voltage divider scheme depending on the position of the wiper of the potentiometer. Whatever signal is left will continue out of the guitar, and return via the guitar jack’s sleeve to the guitar’s internal ground.

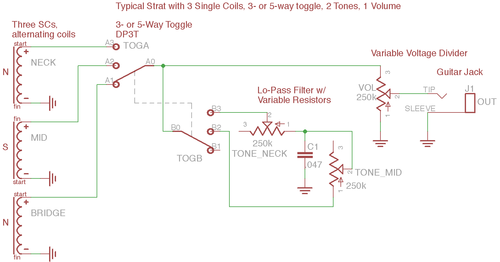

This configuration is much the same as the last circuit, but with the addition of a second tone knob. At first, the pots’ arrangement can look confusing. Remembering that the DP3T toggle switch is set to the same setting on both “sides” can help clear up this situation. When the toggle is at the bridge position, the signal is not passed to the tone circuit. At both the middle position and the “in-between” position of the bridge and middle, only the “MID” tone knob is in a complete circuit, and at the neck position, only the “NECK” tone knob is in a complete circuit. Essentially the corresponding tone knob only is activated when that pickup is activated. When the toggle is set to the “in-between” position of the neck and middle, though, both knobs are active, and are in parallel with each other. The total resistance tends to be closer to the path with the lowest resistance in this situation, and lower than the lowest of the two resistors. So, the tone knobs tend to sound “darker” over more of their range when in this setting.

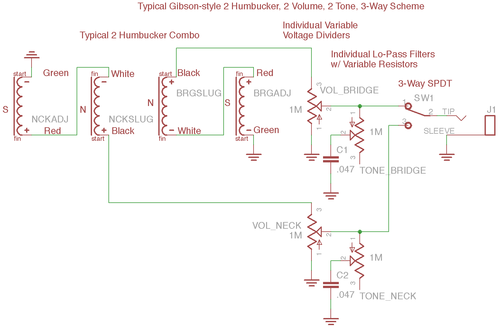

This circuit is a typical Gibson-style circuit with two humbuckers and individual tone and volume knobs for both humbuckers. It is pretty clear to see how the independence is kept of both pickups over much the circuit as the signals do not combine until the three-way switch at the very end. Each humbucker is wired in series within itself. The humbuckers are in a typical parallel setup with each other, with the neck pickup “rotated” so that the north/south pairs of the two humbuckers are equidistant from each other. Each humbucker then goes to its own volume and tone knobs, which are wired in a similar way as the first example. In this case, the volume knob appears first, then the tone. The tone knob is wired “backward” compared to what we saw in the first example, but it works exactly the same way. The signals are then sent to the SPDT switch, which is almost always 3-way to allow an “in-between” setting where both pickups can be summed and sent out the guitar jack. Notice that this passive summing allows some of one pickup’s signal to go through the other pickup’s path. This means that the other tone knob and volume knob will slightly affect the other pickup when in the middle setting. If the volume knob of one was turned all the way down, it would completely short both signals and turn off the guitar.

The next circuit we’ll look at is a non-traditional circuit, containing a number of oddities. It is actually part of the reason I wanted to document and post this information online; I wanted to learn exactly how my Fender Jaguar was wired, and ran into issues trying to find good information about it online.

Anyway, first up is the somewhat strange pickup configuration. I’ve included the color codes, because it is an example of how the polarity of the pickups does not always match what the manufactures claim the color codes indicate. Notice how the output of the neck pickup (PUP2, sorry for not being clear) is the black wire, and the bridge pickup (PUP1) is the red wire. If these two pickups were indeed the magnetic polarities that they say they are, then these two wires would be of opposite polarities, and the signal would be thin when both pickups were active. I rewired the neck pickup to have the red wire be the correct output, and found this to be the case. Combining the two humbuckers definitely sounded better when they were “backwards”. Wiring the neck pickup back to its original specification and testing the magnetic polarity with a simple compass revealed the neck’s magnetic polarity was the opposite of the bridge’s. This explained why the two pickups are wired “backward” from each other, in addition to being physically rotated. The reason for the magnetic polarity flip will become clear in a moment.

The series link within the two humbuckers is connected to a potentiometer in a variable-resistor setup. What this allows is a variable coil-split. When the potentiometer is set to “full”, the single coils are in series with each other like is typically found, and their series-link contains a parallel 50k resistance, which does not affect the signal very much. When the potentiometer is set to “low”, both connections at the series link are shorted to the ground, thus completely shorting one pickup and converting the other to a single coil. How much the single coil effect is heard when the “spin-a-split” is at an in-between state is debatable, however. It is nevertheless a cool tonal effect.

The reason for the opposite magnetic polarities of the two humbuckers becomes apparent when we consider the situation of both pickups set to “single coil mode” and are summed together. In “single coil mode”, the outer single coils are active, and therefore it is desirable for these single coils to have opposite coil polarities and thus opposite magnetic polarities. This is exactly what we see; we are using the start of the South, and the finish of the North (note this is the opposite of what we saw in the pickup discussion page—start of the North, finish of the South—it works either way).

The fun does not end there! The signals are sent to a master DPDT kill switch, which grounds the humbucker’s outputs when killed, or lets both pass. Then both are sent to their own individual kill switches, instead of the traditional multiple-way toggle switch. Then the signals (if both still active) sum directly before a strange-looking tone circuit (at least to the electrical novice) and its associated bypass switch. If you recall the discussion in the tone circuits page, it is simply a hi-pass filter. The bypass switch allows the signal to short around this filter circuit if it is not desired. Finally, the signal passes through a typical tone and volume knob circuit and out the output jack.

I guess it wasn’t so complicated after all; just simply that the manufacturer’s color code wasn’t consistant with what was actually happening in the neck pickup, but whatevs. No biggie.

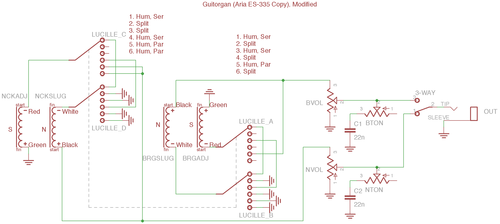

This last circuit is my modified MCI Guitorgan B-35, which was a copy of the Gibson ES-335. For more info on the “organ” part of “guitorgan”, check this out.

The stock layout was a fair approximation of what you’ll find in a standard Gibson: two humbuckers in series with themselves, parallel to each other; three-way pickup selecting switch; volume and tone knobs. The biggest oddity was this 4P6T 6-way switch that was supposed to emulate the somewhat elusive Vari-tone or “Lucille” switch found on many ES-335 and similar models. Originally, this switch made 6 different tone settings available, using various combinations of capacitors, resistors, and a “choke” (aka an inductor). But frankly, the Aria version of the Vari-tone just sounded, well, crappy. I always kept it at the first position, and I thought the other positions just made the tone sound thin and harsh. Occasionally I could use them for lo-fi effects, but there are a lot more effective methods for creating such an effect, in my opinion.

I decided to rewire the 4P6T switch for more useful purposes. I find the various combinations of pickup wiring to be the more effective tonally than passive filters. The 4P6T allows me to control 4 different signal paths with 6 different outputs, so this allowed 6 different combinations of the individual coils of the humbuckers. I arbitrarily decided which wiring schemes to use, and wired the switch accordingly (they are listed in the schematic above). Technically, I’m only using three different wiring schemes: humbucker in series, single-coil, and humbucker in parallel, but the various positions alter how these are combined when both pickups are in use, allowing for 12 unique tone settings between the Vari-tone and 3-way pickup selector alone.

Other than the 4P6T, the Guitorgan is wired in a fairly standard way, similar to the “Gibson” wiring style seen above.