home | tumblrblog | musics | electronics | ask | about | more

The typical switches you find in most guitars are simple in theory: they usually have a few possible positions, so you might assume that, electrically, they might only have an equally few number of wires going to them. But, if you are not already familiar with electrical switches and you open up your guitar, you may be surprised when you find that the wiring doesn’t seem to match what you think it does. Switches and toggles are a little more complicated than you might initially assume, but once you understand their operation and why they are the way they are, then things start to make a lot more sense. And, there are only a handful of switches that are actually used, so it’s easy to memorize their functions. Let’s start simple and get more complex.

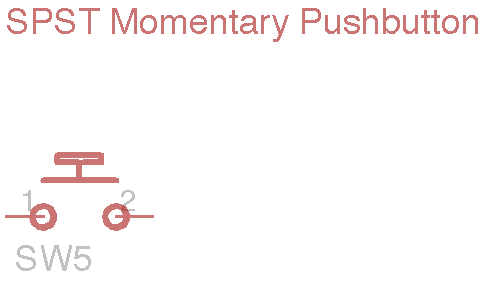

The simplest possible switch is a momentary pushbutton. They can either be normally open (NO)—meaning that there is no connection until you press the button—or normally closed (NC)—meaning it is always connected until you press the button, then the connection is broken. Often the housing of a pushbutton hides its operation, so the easiest way to know what type it is is to do a short test with a multimeter. The official name for this kind of switch is a Single-Pull, Single-Throw (SPST). This means that you only move one mechanical thing when you use it, and that mechanical thing can only connect to one contact. Notice this does not describe the number of possible positions; technically this type of switch has 2 positions, but only one connection—more on that topic later. These pushbuttons are generally only used for kill-switch effects that let you turn on and off you guitar quickly, though they may be used for whatever you can think of.

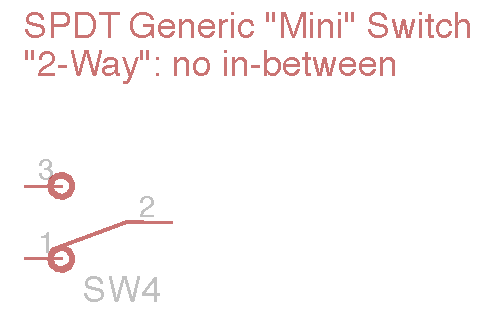

The next type of simple switch is sometimes called a “2-way” toggle or mini-switch. “2-way” describes the number of possible positions. It’s official name is a Single-Pull, Double-Throw (SPDT), meaning that you only move one thing, but it has two possible connections. This is useful for bypassing parts of a circuit, or switching between two possible circuits. Sometimes they are found as toggles for pickup selection that do not allow for combining the pickups’ signals together; it is either one or the other. This is somewhat rare. More commonly they are used for simple pickup configuration switching, like including or excluding a coil-tap. You can also leave one end not connected (also NC) and use it as an on/off switch, much like the momentary pushbutton but with a latching effect.

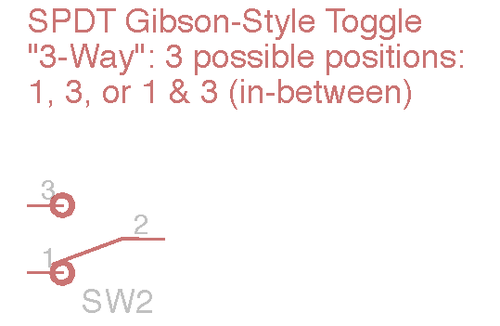

Related to the “2-way” mini-switch is the Gibson-style “3-way” toggle. I call this switch “Gibson-style” simply to contrast with the Fender-style toggle we will discuss in a moment. These toggles are usually used for pickup selection. They are SPDT switches like the “2-way” mini-switch, but they have 3 possible positions. The third middle position is “in-between” the outer two positions and combines them together. This way you can use both pickups at the same time, for example. There are other uses for this switch, but this is the most typical.

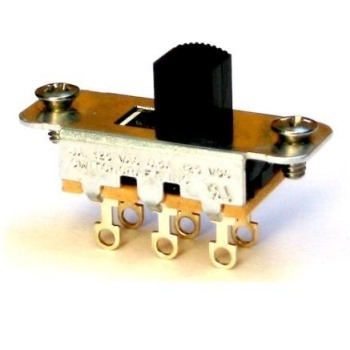

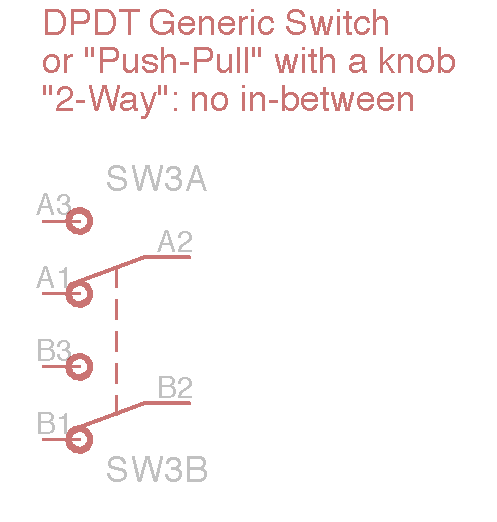

A very common switch is the generic “2-way” DPDT. This is usually in the form of a two-position switch or a push-pull switch found on many pickup selectors and volume/tone knobs. The DPDT stands for—as you probably guessed—Double-pull, Double-throw. This means two separate things are moved when you flip the switch, and those switches have two possible connections. These usually cause those who are unfamiliar with circuitry the most confusion, but sitting down and testing where the connections are made with a multimeter is the best way to learn. A “3-way” DPDT is also possible which allows for a third middle position that connects the connections together.

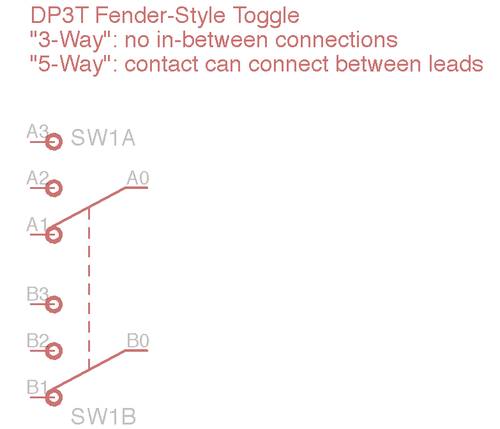

Finally, we have the Fender-style DP3T, which can be “3-way” or “5-way”. The “3-way” version can be found in Teles and old Strats, where in the Strat, the three positions selected which of the three pickups was in use, and in the Tele acted like a Gibson-style “3-way”. Eventually the “5-way” switch evolved for Strats, which allowed combinations of the neck and middle pickup or the middle and bridge pickup. Remember, with a multiple-position switch that only has a few possible connections, the additional positions represent an “in-between” state that connects adjacent connections together.

Many more switches exist with increasing complexity, but understanding the basics makes learning how these more complex switches work much easier. For example, you sometimes find a rotary “6-way” DP6T switch on some Gibsons that switch between 6 different tone settings, sometimes called a “Lucille” switch. Knowing that because the number of positions equals the number of throws, there are likely no “in-between” settings, and deducing a pinout for one of these is easy with the help of a multimeter.